When the 15th-century Genoves naval captain, Lanzarotti Malocello, discovered an island one-hundred miles from the coast of North Africa he decided to bequeath his name to posterity and promptly named it Lanzarote. It may have been good for him but it wasn’t so good for the islanders as a few decades later it was a centre of the slave trade under the Castillian crown, with most of the indigenous population falling victim to slavery with many dying at the hands of merchants and pirates.

As if slavery wasn’t bad enough, in 1730 the island experienced one of the world’s greatest volcanic eruptions, lasting six years, (it has had a number of them over the centuries), burying more than twenty villages and leaving the island with a unique landscape, more of a moonscape really, that from a distance looks like new and unevenly turned earth.

The luna landscape is most evident in the dramatic Timanfaya National Park where over one hundred craters display tones of ochre and grey to a backdrop of the piercingly blue Atlantic. As you take a ride through the surreal landscape you half expect to see Neil Armstrong step out from behind a rock in a big white bubble moon suit. It comes as no surprise to learn that many of the scenes from Planet of the Apes where filmed here.

Adaptable as ever, though, the north of the island shows how man can turn even the most extraordinary environment to agricultural use. To grow the grapes for Lanzarote wine (the best said to be the excellent white from the 18th century El Grifo winery), first the farmer must dig a hole to the bare rock below ground. This is then covered with a layer of sand over which soil is laid. Once the vine is planted the soil is covered with la pili, the black volcanic sand that stores water and releases it through the night, negating the necessity of irrigation, a high priority in a dry, flat, barren island. To protect the vines low walls are built around each three plants, giving the impression of an enormous black and green quilt laid over whatever dragon might be below ground, ready to exhale his fiery breath once more. Step into one of the small walled enclosures and it’s like walking into a fireplace once the coals have cooled.

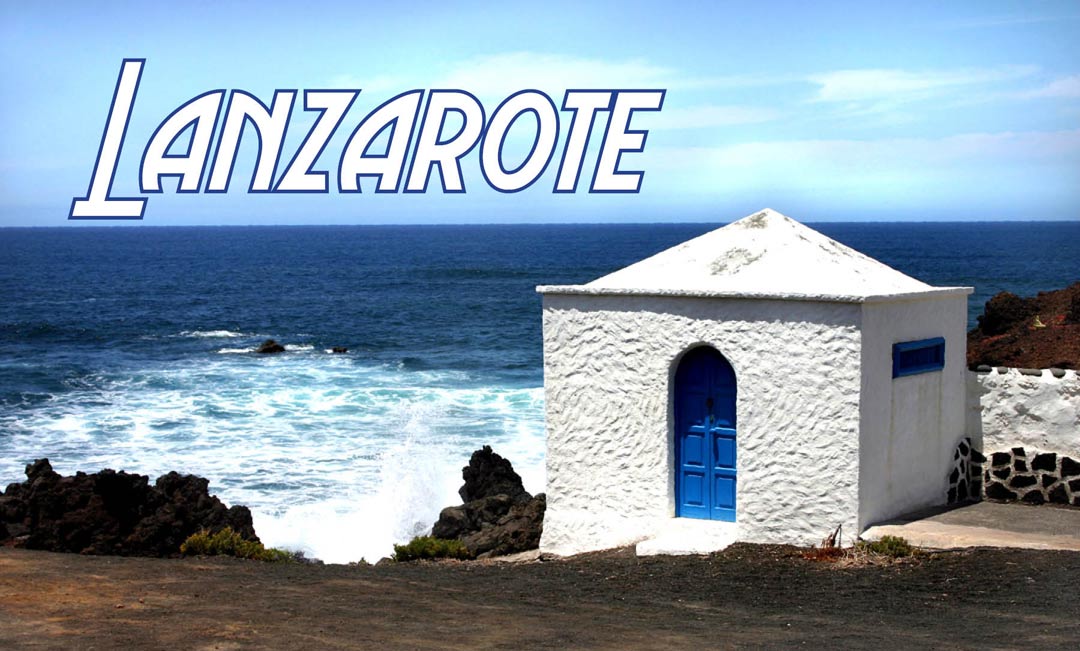

Little breaks the long views of volcanic landscape. Squat one- and two-storey houses with flat or pointed roofs are scattered like sugar cubes. Island laws say that all houses must be white and woodwork can only be painted in green, brown or blue, and that also depends on whether you are either near the coast or further inland. But the limited colour palette is enlivened with bright red hibiscus growing in the gardens of black ash.

In 1993 Lanzarote was named a Biosphere Reserve by Unesco, in an attempt to unite the socio-economic development of the island with conservation of the natural resources. To promote the rural areas of the island the “Asociación de Turismo Rural de Lanzarote” (Rural Tourism Association of Lanzarote) was created in an attempt to make it possible to get to know the island, its culture and its people in an everyday setting.

All rural accommodation must be at least 50 years old. To encourage the restoration of the existing architectural heritage no new building is allowed. The Associación is actively encouraging a new type of tourism on the island, which includes equestrian tourism, bicycle tourism, walking holidays and discovering the local cuisine.

Being a hop of just one hundred kilometres to the Dark Continent probably explains why north Europeans flock to the island in the darkest months of the year. Winter sun is guaranteed.

Leave A Comment